Pricing models never made headlines until freemium came along.

Praised as the fuel for rapid growth of companies such as Dropbox, Spotify, and Evernote, and lambasted as the reason smaller companies went bankrupt, freemium has piqued the interest of developers and CEOs who hope to get as many people possible hooked on their products as possible.

Freemium is free + premium: a good or service that can be offered for free, but ramps up to include premium features that cost money. The concept is basic and widespread: entice enough curious people, accept some early losses, and win over a few remunerative customers for life. An ice cream truck offers free samples; some people stop by to try a flavor, some just take a bite and leave, and others buy large cones for the whole family every summer for generations.

Often the path to buying software is not as direct as ordering soft-serve. We want to clear the air about freemium and its place in the SaaS landscape. We'll look at why it works, what happens when it breaks down, how profitable companies have made it fit into their longterm goals, and what the future holds.

This is our Freemium Manifesto—what we consider the right way to do freemium. Consider this guide the final word on how to make freemium work in SaaS from the people that have seen inside more SaaS companies than anyone else. Freemium does have its pitfalls, but done right it can work beautifully to get users into your ecosystem and on the path to upsell.

To start us off, we want to see where it all started. Let's look at why companies started offering products and services for free.

Freemium in its infancy: 1982-2000

The freemium model as we know it now can be traced back to the early eighties, gaming culture, and a few press-savvy developers.

Freeware and Shareware

In 1982, an editor at PC Magazine,Andrew Fluegelman, wrote a communications program called PC-Talk. It was a great little program. PC Magazine, perhaps unsurprisingly given its editor, said PC-Talk "is elegantly written and performs beautifully. It is easy to use and has all the features I would expect from a communications program."

But the interesting thing about PC-Talk wasn't the software, but the way it was sold. Or rather, the way it wasn't sold. Fluegelman distributed the program via a service called Freeware. Anyone who sent him a disk in the mail would receive the program in return, and could copy the disk for friends. If they liked it, they could mail Fluegelman $25.

He called it this: “an experiment in economics more than altruism.”

Though slightly different to the model we see today, freeware incorporated the fundamental tenet of freemium: only pay when you get value. If you never liked PC-Talk, you were free to have it for free (minus shipping and handling).

Around the same time, IBM developer Jim Knopf created a program he named PC-File, and followed the same model. He observed, “Here was a radical new marketing idea, and the computer magazines were hungry for such things to write about," he explained. The result: "much free publicity for PC-File."

Fluegelman and Knopf had uncovered the essential nature of freemium: it's a marketing strategy first and foremost.

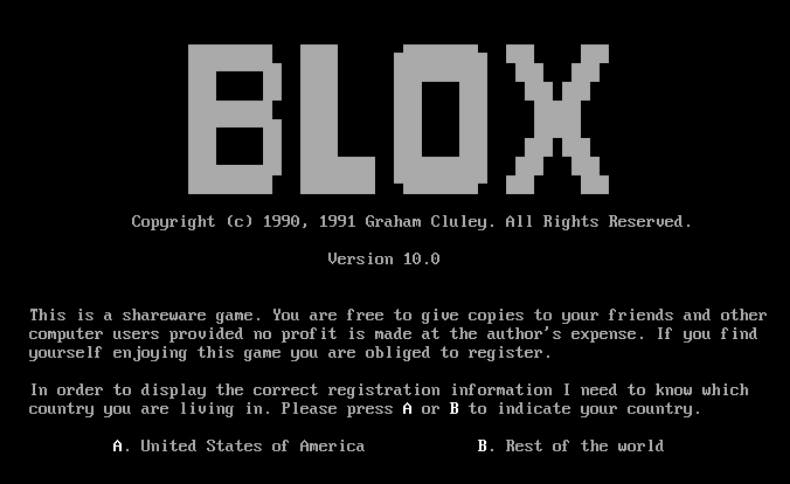

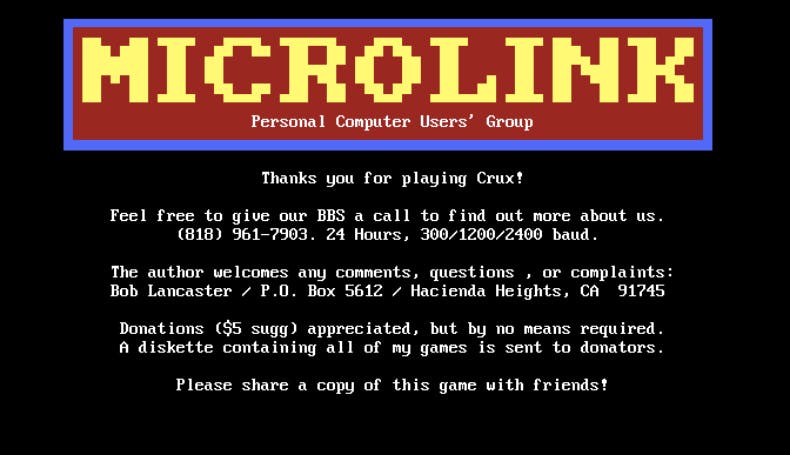

Where utilities went, games followed. Freeware's model was embraced by gamers who were eager for others to try out their creations. Indie developers mailed floppy disks of games called shareware for other enthusiasts to try out. These disks were later aggregated into catalogues and larger disks for distribution.

Shareware fit into the gaming culture of good will, knowledge-building, and collaboration that was in tandem with the growing open-source development movement (though it's important to note that both freeware and shareware do not make source code available). It's doubtful that software would be as advanced as it is today without those who made their products free.

Screens from Blox and Crux, shareware games created for MS-DOS [source]

These DOS games and applications allowed anyone to try them for free. More than that, they hadperpetual value. In this sense, they were truer to the real idea of freemium than a lot that came afterwards. PC-Talk, PC-File, Blox, and Crux gave you access to free software and games forever.

Unfortunately for their inventors, they hadn't really figured out the upsell.

The rise of the internet

In 1995, journalist Esther Dyson asked an important question about the burgeoning web: What new kinds of content-based value can be created on the net?

Dyson observed that as the web becomes populated with all kinds of content including executable software, business data, and entertainment, games, and news, intellectual property will depreciate in value.

“The likely best defense for content providers,” she argues, is “to distribute intellectual property free in order to sell services and relationships.”

Boom! In that one sentence Dyson created the most prolific business model of the next two decades: freemium. Distribute some IP for free to get people to pay for something else.

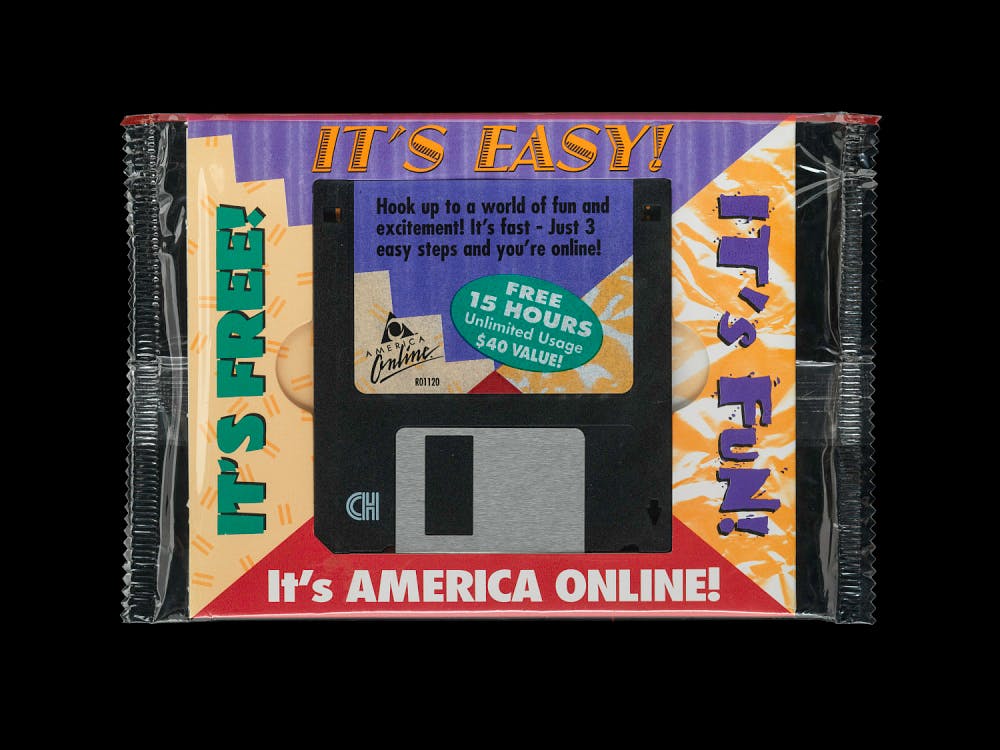

But even by 1995, one company was already making significant headway with this idea. Give a little away in the short term to get a lot back later: AOL. Anyone over a certain age will remember opening their mailbox one morning in the mid 1990s to find an unsolicited disk.It's free, it's easy, it's fun—it's America Online.

The USPS dropped millions of AOL disks in mailboxes around the country, as other postal services did worldwide. Each disk contained a few hours of free time online for users to spend emailing, chatting, and reading the news. Just long enough for you to get hooked on the world wide web. AOL's stunt was so memorable and prolific that the disks are now on display in the Smithsonian.

Then came the upsell.

After your 15 hours were up (in the early days, as they transitioned to CDs, you got 1,000 hours free for 45 days!), you had to start paying at about $14/month for continued access. But it worked. From 1992 until 2002, the number of AOL subscribers grew 125X, from 200,000 to 25,000,000.

It worked because AOL had the unit economics done. Though they spent over $300M on disks and CDs, their LTV:CAC ratio was 10:1.

AOL employed the shareware method to bring its suite of services to the mass market in the early days of internet growth. Unlike shareware, however, the disks contained an expiration date, and were not copyable. This isn't yet freemium. Now there is the upsell, but no perpetual value. This model would also become common in SaaS—the free trial.

Boom and bust: 2006-2017

Fast forward to the mid-aughts. Dyson's projections prove accurate, and the web is saturated with free content. Bundled service providers like AOL have phased out and cloud-based subscription services are enjoying their time in the sun.

Enter software-as-a-service. The smartest SaaS providers realized early on that it's not enough to build a product that is novel or useful; the most valuable products need to have compounding value over time, built-in network effects, and a high-performing infrastructure. Even so, people still expect all kinds of online content, including services, to be free. At least, at first.

Venture capitalist Fred Wilson notices a trend among fast-growing SaaS companies and extols the method on his blog:

“Give your service away for free, possibly ad supported but maybe not, acquire a lot of customers very efficiently through word of mouth, referral networks, organic search marketing, etc, then offer premium priced value added services or an enhanced version of your service to your customer base.”

Wilson calls it his favorite business model, and points to examples such as Skype, Flickr, Trillian, Newsgator, Box, and Webroot as paradigms. At the end of the post, Wilson says:

I would like to have a name for this business model. We’ve got words like subscription, ad supported, license, and ASP, that are well understood. Do we have a word for this business model? If so, I don’t know it.

Thirty-three comments and much debate later and Jared Lukin, then of Alacra, wins with his term for this business model: freemium.

At the time, these companies all had seen explosive growth at one point or another. And in pre-recession Silicon Valley, growth-at-all-costs was trendy. Wilson, like other VCs at the time, was impressed by large usage numbers and less concerned with monetization. Profits would follow, they assumed, once developers and marketers got everyone and their friends using their products.

Let's look back at the companies listed by Wilson to see what their business models were then compared to now:

- Skype: Basic in network voice is free, out of network calling is a premium service. Acquired by Microsoft in 2011, Skype basically still operates on the same freemium model. You can make Skype-to-Skype calls for free, but have to pay to call regular phones. Skype for business is $5/user/month.

- Flickr: A handful of pictures a month is free, heavy users convert to Pro. Again, the same model for the most part.

- Trillian: The basic service is free, but there is a paid version that is full featured. There appears to still be a free version of Trillian for personal use, but the company doesn't want you to know about it. If you go to the Trillian pricing page, it defaults to business pricing with the lowest price for business users being $2 per user per month.

- Newsgator:The web reader is free. If you want to sync with outlook and your mobile phone, that’s a paid service.Newsgator is gone. What was an RSS aggregator in 2006 is now an internal messaging app for your company in 2017, called Sitrion. Either way, freemium is gone along with all self-serve pricing on the page. Now you have to contact the sales team to even see the product.

- Box: You get 1gb of virtual storage for free, but you have to pay for more than that. You can still get storage for free as an individual with Box, and they've kept with the times upping the limit to 10GB. There is no freemium for the business version, only a 2-week free trial for your team.

- Webroot: You can get a free spyware scan, but for full protection you need to pay. Freemium has gone for both home and business use. The smallest plan is now $29.99 for one device for one year.

From those six companies:

- Two look the same, with freemium option intact (Skype, Flickr)

- Two have freemium, but are hiding it (Trillian, Box)

- Two have removed the freemium option altogether (Newsgator, Webroot)

Over time, while many of these companies successfully expanded their network effects, others have obviously struggled to find a freemium structure that's sustainable. Two companies that were the doyen of the freemium movement, Flickr and Evernote, typify the struggles that this model can elicit.

Flickr's pricing trip

Flickr's pricing now looks the same as 2006, but their pricing structure has changed time and again over the last decade to find a happy medium between revenue growth and user growth.

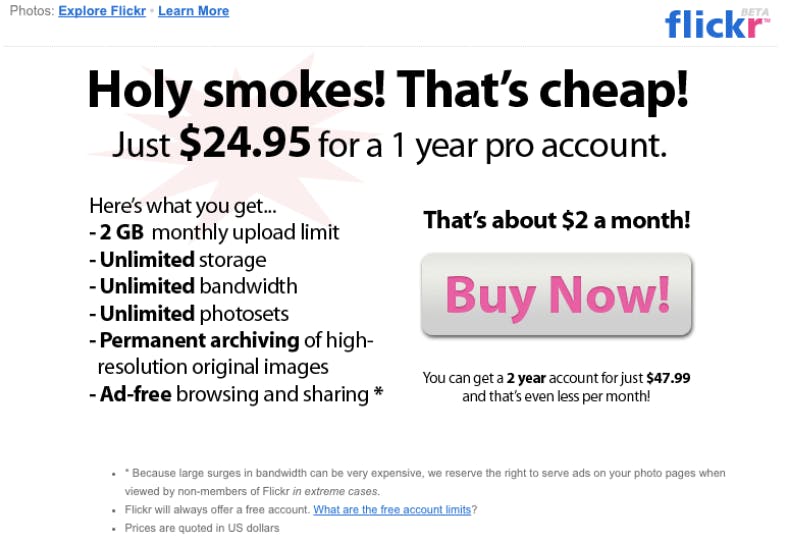

As other photo services have gained traction. Acquired by Yahoo! in 2005, Flickr was the first social platform based around photos, Flickr has struggled to add value to its core product. It started as a free product with an option to upgrade if users wanted to upload more than 1GB per month. While still in beta, they switched the pro plan to $24.95 annually and added another GB for uploads, which stayed more or less the same for several years.

Flickr upgrade page in 2006.[source]

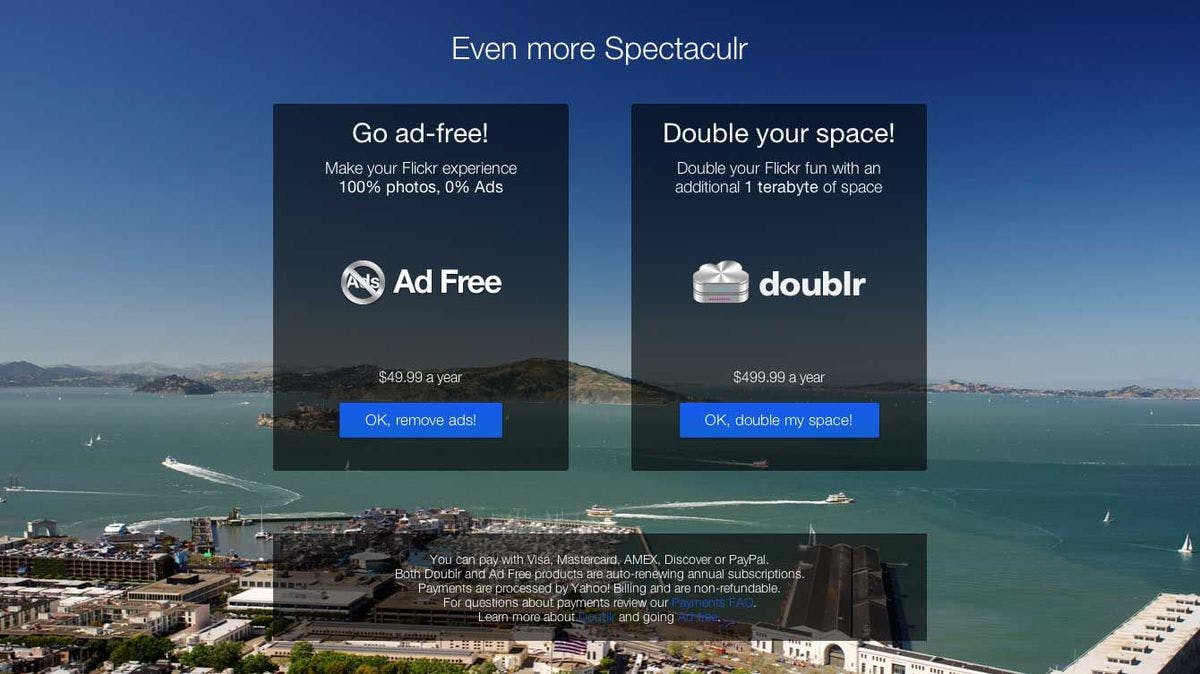

Over time, Flickr experimented with allowing free users to only upload photos that were up to 10 MB in size, or up to 20MB. They limited the number of photostream items to 200. In May 2013, Flickr moved almost completely to anad-supportedmodel. Most pro features were made available in the free plan. Legacy pro users could keep their accounts, and there were still upgrades, but they were vastly more expensive and largely unnecessary, even for power users.

Flickr in 2013.[source]

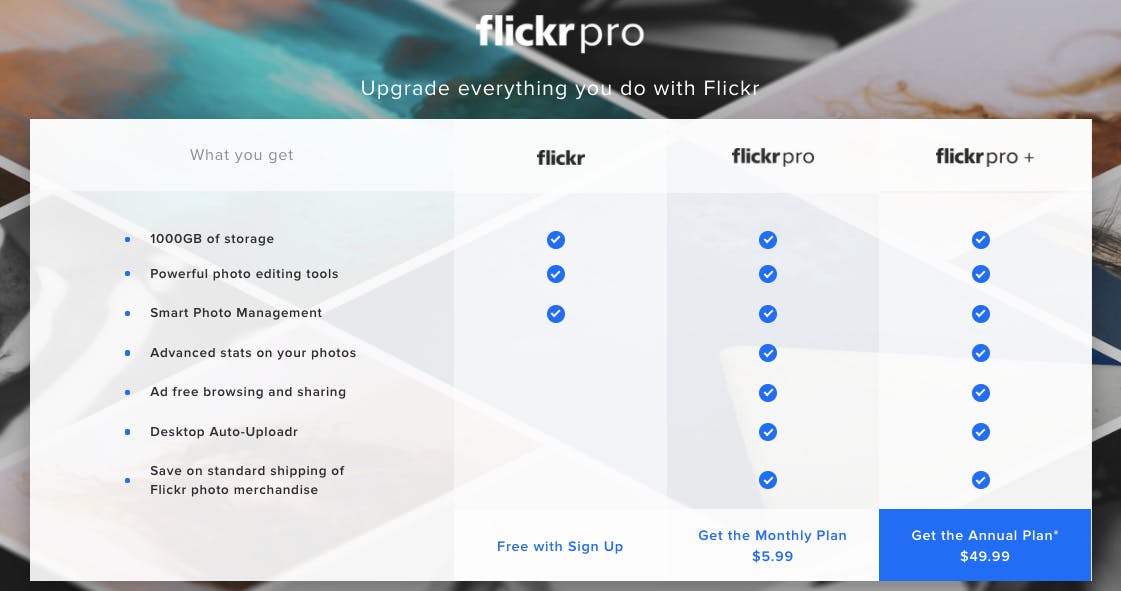

These changes were unpopular with users, and a new pro plan was reinstated in 2015. The Flickr upgrade page now looks like this:

The new pricing page shows a clear difference between the plans, with notable value-adds for power users, and prices that are simple and gimmick-free. However, it may be too little, too late, for fed-up customers.

One of the problems with Flickr's pricing changes is the way they took away previously available features. This led to users getting annoyed by paying for things they expected to be free. In some cases, when users stopped paying, Flickr would hold photos “hostage,” until the pro fee was paid.

In 2015 Flickr released the Auto Uploadr, a tool that allowed users to upload batches of photos, among other things. By 2016, the tool was restricted to paid users.Wiredsaid the move felt “a bit like ransomware.”

By that time, Flickr was no longer the best and only photo-sharing site, and competitors such as Google Photos, 500px, and Instagram offered the same functions for free, with no threat of removing them.

Evernote's lack of focus

Evernote was another product that spread like wildfire in the mid-2000s. When it launched as the first cloud-based notes app during the recession in 2008, its founders didn't raise much venture capital. Instead they relied on word of mouth referrals, the opening of the App Store, and freemium to grow to 75 million users and a valuation of $1 billion by 2013. In a 2011 talk, former CEO Phil Libin called his customers his marketing team and said, "The easiest way to get a million people to pay for nonscarcity product may be to make 100 million people fall in love with it." In 2014, they surpassed that 100 million mark.

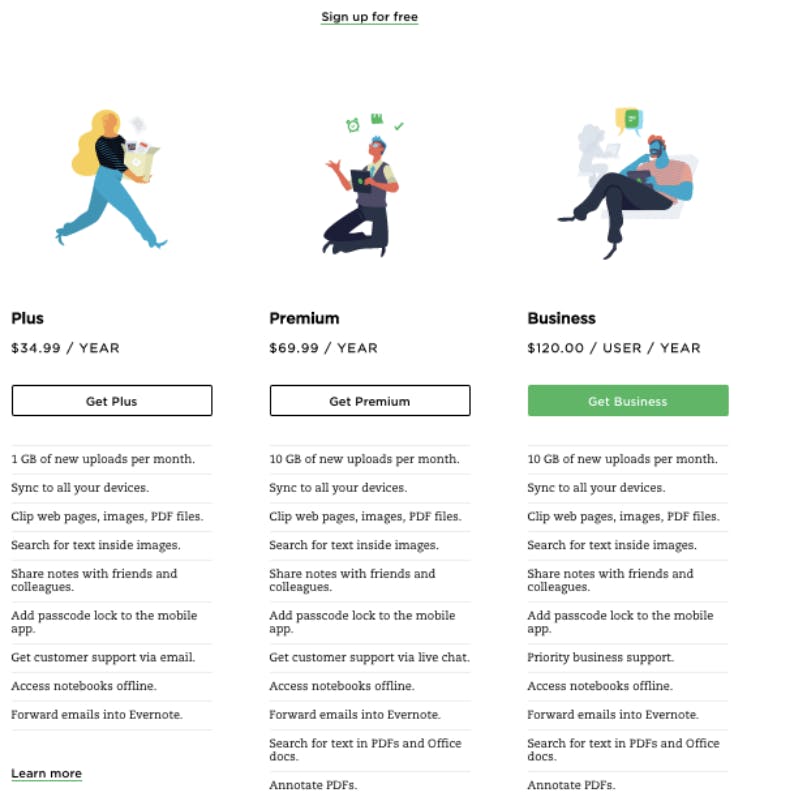

Evernote has a beautifully laid out pricing page, but most users don't even look at it. [source]

However, as Libin proudly noted, they have pursued a conversion rate that hovers around 1%. They continue to put enormous effort into their products, and yet millions of people don't see a need to upgrade. A 2015 Business Insider article shows why:

"Instead of focusing on its core note-taking product and on converting users to the paid service, Evernote spent more time releasing a bunch of new products and features that only helped it grab news headlines."

Despite 150 million users at the time, Evernote had to lay off 18% of the workforce and close 10 offices. While the management team focused on partnerships with Post-it Notes and Moleskine, the actual product became secondary.

Ironically, the Evernote team was pursuing a strategy that can work beautifully. Upsell other products adjacent to your core product. This way, Evernote can increase revenue not just from their 1% conversions, but also from free users who want a nice leather-bound notebook for their written notes.

But in doing so, they forgot two things:

- Continuing to offer the core value through the app to dedicated users

- To understand their customers and what really drives them to use Evernote

Users didn't want a nice notebook, they wanted a working note app. They also didn't need to be sold on minor improvements. Rather, Evernote needed to emphasize what kept them ahead of all other cloud-based note-taking apps, and what value they offered to loyal customers. For instance, could they use machine learning to predict what you might want to write as you continued to jot things down over the years? Had Evernote made the core product more valuable to paying customers, they might not have struggled with revenue.

The future of freemium

It seems that freemium, like freeware, is still an experiment in economics. Just like freeware and its descendants dovetailed, freemium and free trials are now becoming distinct models. Free trials are more like advertisements — they offer a test-drive to those who need an interactive experience to be convinced. Freemium is about creating value from the start via personalized pricing tiers for specific user profiles.

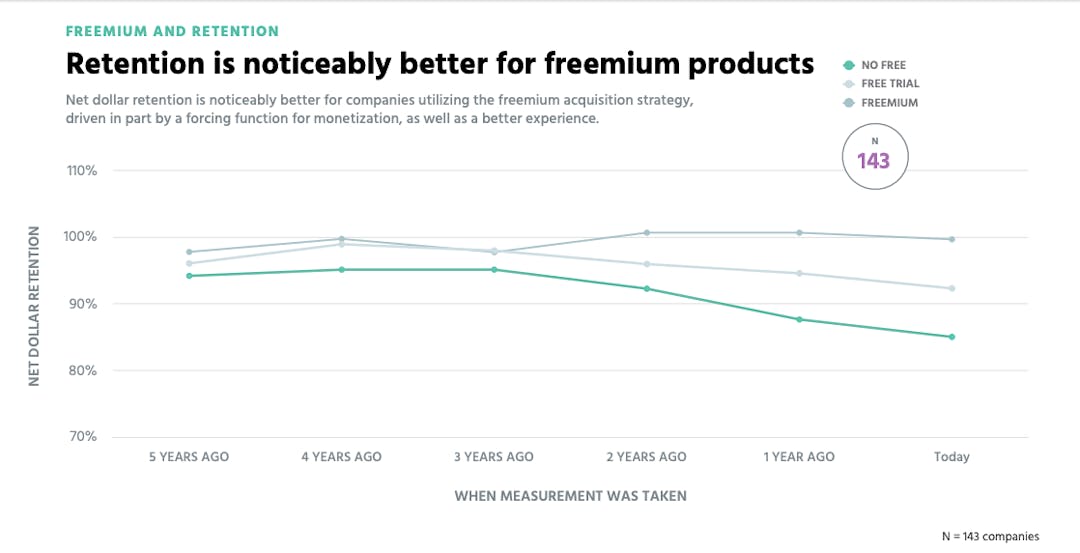

And when done right, freemium allows a company to monetize properly. By gaining a greater understanding of its position within an industry, a freemium company can maximize its longterm value while reducing customer acquisition costs.

As an understanding of the freemium model has evolved, the SaaS sector has realized what doing freemium right means: getting to know your customers first and continuing to offer perpetual value whichever plan they are on.

MailChimp: Free, but still valuable

MailChimp took a measured approach to freemium, working for years with customer data to ensure that the products they built matched what every user wanted and needed.

MailChimp CEO Ben Chestnut made a point of saying that the company was not a startup when it launched a free plan, 8 years after its founding. In those 8 years, they tried out freemium variations such as pay-as-you go vs. monthly subscriptions, and free trial vs. free forever. By the time they went freemium in 2009, the core email product was both affordable and profitable. They had recently saved on server costs by switching to the cloud.

They named their first free plan “Forever free,” and the exact wording is still on their pricing page today. It's used by new businesses, non-profits, and small organizations. And if you're not sending a large volume of email, it's an excellent service.

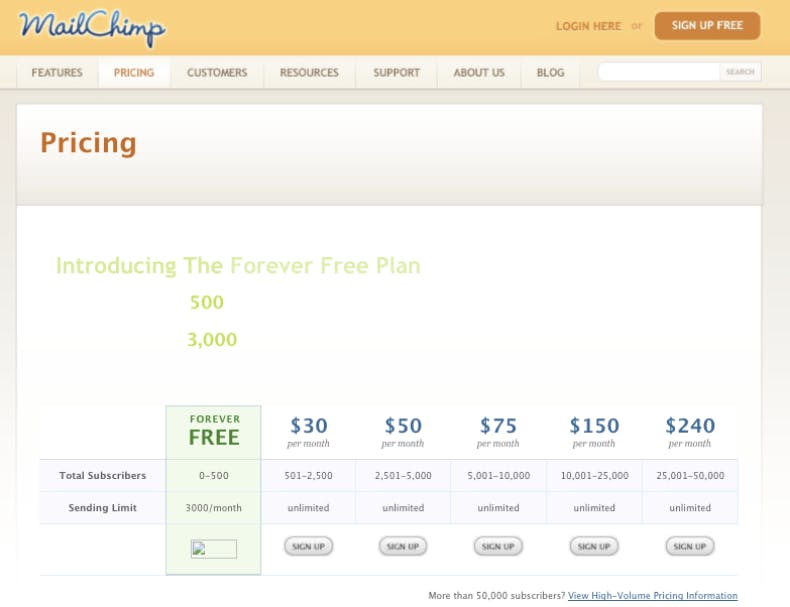

MailChimp pricingpage in late 2009 [source].

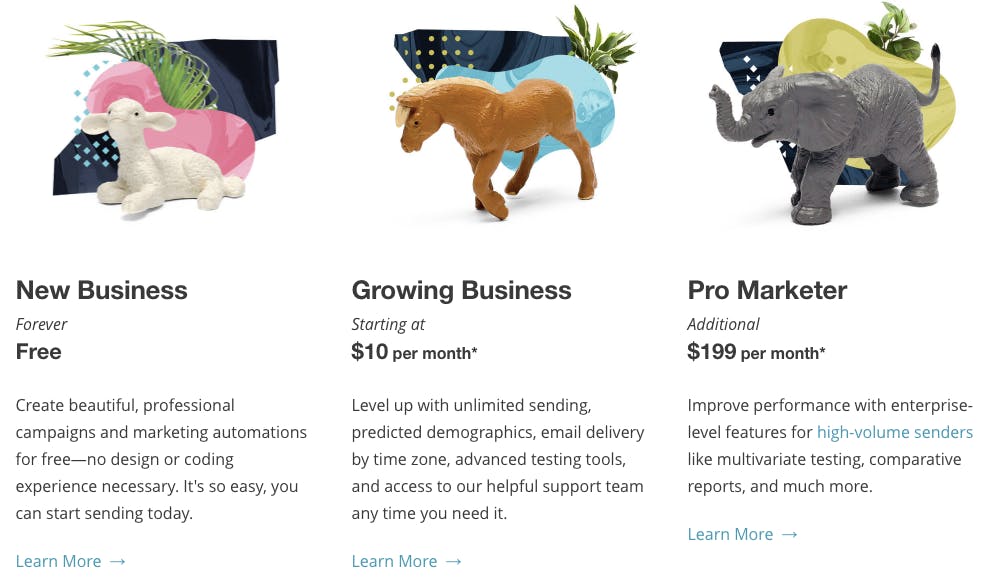

MailChimp pricing page today. [source]

A year after launching Forever Free, Chestnut wrote another blog post with the following data (h/tDrift):

- MailChimp had grown its user base 5x, from 85,000 in September of 2009 to 450,000 in September 2010.

- They were adding more than 30,000 new free users and 4,000 new paying customers each month.

- Profit had grown 650% (!)

- CAC had decreased 8% in just the last quarter to under $100 (main reason for profit growth).

MailChimp had not only created more value for more people, but they had increased their profits in the meantime. And more MailChimp emails were out in the world than ever before, meaning that people were sending better email, regardless of cost.

ProfitWell: perpetual value

One of the constraints most freemium models above impose on user is a value metric limit. Whether it is the storage limits of Flickr and Box, or the subscriber or email limits of MailChimp—at some point the product becomes unusable for these users without the upgrade.

This is, of course, part of the point. At these limits it is assumed that users are getting enough value that they will want to pay for the service for continued use. But the low conversion rates on all freemium show that this isn't always the case. That is why we advocate for perpetual value in freemium.

The core value should be free for whoever you are—a single user or a 1,000+ team. This is slightly akin to Skype's freemium model, at least for individuals. If you download Skype you can use the core value, calling other Skypers forever, for free.

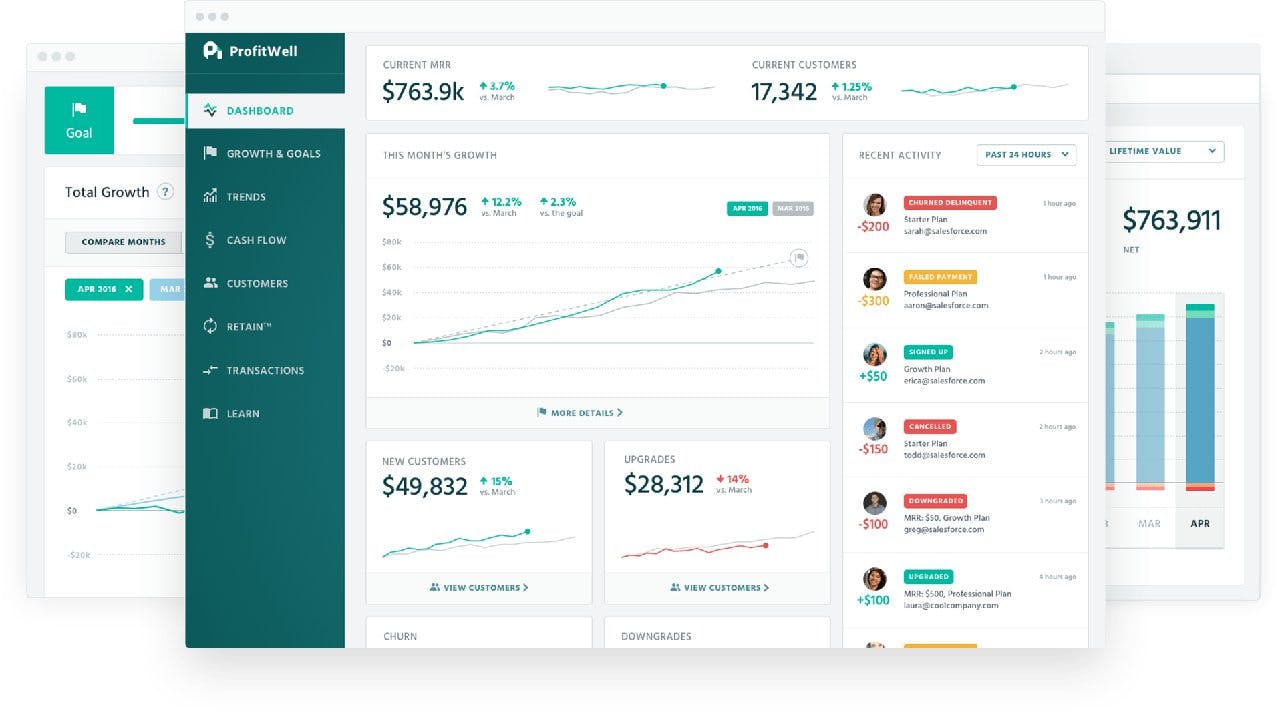

This is the model we want to build and that we want others to build. In ProfitWell, we want a product that is useful for any size of SaaS company, whether you have one customer or 1M, and can be used by you alone or a 1,000 member team. There is no value metric limit.

The upsell comes from adjacent products to the core value. The core value of ProfitWell is understanding your analytics. The premium part of our freemium comes from helping you do something with that information. For instance:

- Retain recovers delinquent churn(that you identified through ProfitWell Metrics) using in-app messaging and email reminders to customers

- Recognize allows you to convert your subscription revenue (which you manage through ProfitWell) into GAAP recognized revenue.

If you don't need to recover churn or don't need to recognize revenue, then no worries. ProfitWell will continue to be entirely free for you. But if you are using ProfitWell properly and getting value from the product, you will need these things. You'll understand your churn and want to stop it. You'll grow your revenue and need to get your finances straight.

In perpetual value freemium, the perpetual value leads to upsell even without a value metric.

We think any company can do this. They can offer constant value to customers whether they choose to pay or not, and still generate revenue through upsell linked to their core value. For MailChimp this might be new email designs or delivery analytics. As long as the core value is there, there is a way to upsell something that just makes that core value richer.

Freemium, done right, works

As more companies learn how to work out the kinks in their free models, we'll have more ways to think about pricing innovation, which, as a business intelligence company, is obviously very exciting to us.

More importantly, as freemium companies continue to adapt both their products and pricing, and continue to make software accessible and available to all, we can see what it takes for a software company to truly create a lifetime of value. We think that a lifetime of value comes from offering value for a lifetime—perpetual value. History will see if we are correct.